A Path to Change

In all likelihood, you are one of half of Americans who makes a resolution on New Year’s only to forget about it within months, weeks, or even days. Why is it the case that the people who make these vows are usually sincere about wanting to change? Whether it is eating better, exercising, or repairing an estranged relationship, the desire for improvement is real. A University of Scranton survey in 2013 found that only 8% of people who made New Year’s resolutions satisfactorily achieved their goals. There are many reasons for this high rate of failure, but statistics indicate that an unbelievable 80% fail by the first week of February.

From my perspective, one of the reasons for this high rate of failure is that we don’t really perceive New Year’s as a time of personal transformation. While wearing funny hats and blowing party horns are considered an essential part of the New Year’s experience, working on personal growth is not.

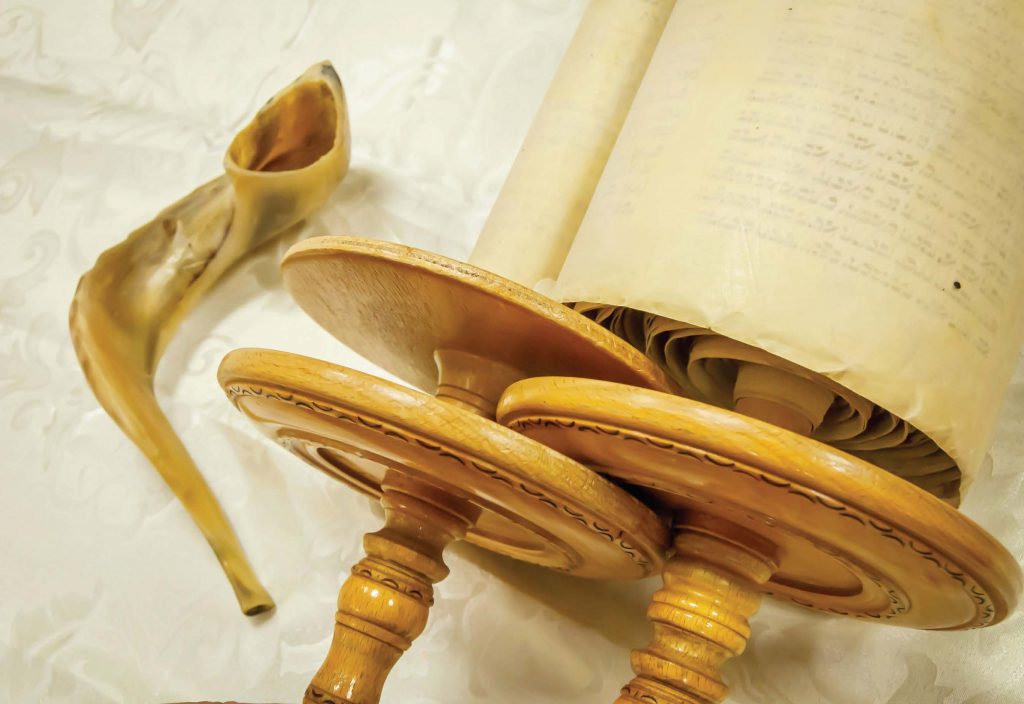

In contrast to our American celebration of New Year’s, the Jewish new year, Rosh Hashanah, is seen as the beginning of a process filled with resolutions and self-reflection. The 10 days from Rosh Hashanah that culminate on Yom Kippur are known as The 10 Days of Repentance and are more commonly known as the High Holy Days. This period begins on Rosh Hashanah with the joy of welcoming in the new year. With festive meals, apples dipped in honey, and the blowing of the shofar (ram’s horn), we celebrate the precious nature of time. According to a 2000-year-old

rabbinic tradition, Rosh Hashanah marks the day on which Adam and Eve were created. We therefore are celebrating not only the gift of life, but creation itself. When the apple is dipped in honey, a blessing is recited praying for a year of goodness and sweetness.

On Rosh Hashanah, Jewish people greet one another with the expression “shana tovah”—“a good year” (some people say “l’shana tovah”)—a type of wish that we will all have a year of goodness in our lives. But many people don’t know that the full greeting is “l’shanah tovah tikateyvu”—“may you be inscribed for a good year.” It is a reference to the Book of Life and the idea that our deeds are recorded in this book and our actions will determine the kind of year we will have. But in truth, the advent of Rosh Hashanah does not mark the end of our story for the year. We are given the opportunity to write an epilogue for 10 days to create a different conclusion. During these 10 Days of Repentance, we are supposed to reread our “book” that has been recording our deeds and determine what actions we need to atone for and in what ways we need to change our lives for the better. This process of teshuvah (the Hebrew word for “return”) requires that we recognize these wrongful deeds (in religious terms, we often call these sins), express regret to those we have wronged, and actually make amends when possible. For nine days, we are supposed to focus on the process of transforming whom we are; it is this epilogue to our book that will determine the kind of year we will have. For those of us who don’t believe that God will actually punish us for our misdeeds, there is the belief that our deeds determine the lives we live. It is the idea that our actions create consequences that will serve as the framework of our lives (some people call this karma); by changing our deeds, we change our lives.

On Yom Kippur, we initiate the most serious part of the process of change by fasting (thereby demonstrating our sincerity), and during services, we symbolically stand before the Heavenly Court to plead our case. Have we shown true remorse for our mistakes? Have we truly begun to change our lives? Are we moving in the right direction? And the most important question of all is: Do we deserve the precious gift we call life?

When taken seriously, the process of teshuvah that takes place during the High Holy Days is much more likely to elicit personal change than the resolutions promised on New Year’s Day. The Ten Days of Repentance allow us the opportunity not just to promise change but to reflect on the patterns of behavior in our lives that lead us to bad decisions and to see the bigger picture of what we need to change.

We live in a world in which people have become immune to the power that words have in shaming people that brings real pain. We live in a time in which social media provides a platform to bully people from a safe distance. We live in a community in which people are often valued (and treated) according to how much money they have or how many “likes” they have on social media. Most recently we have lost the ability to hear each other. We refuse to acknowledge that someone with a different political view than ours can have anything valid to say and believe that he or she is unworthy of our friendship. If these types of actions don’t represent a need to change, I don’t know what does.

What does it mean to have a shanah tovah—a year of goodness? It means that we do our part to bring goodness into the world. How much goodness do you bring? Can you bring more? This is the potential of the High Holy Days.

On these High Holy Days, I pray that we all reflect on the ways that we can change ourselves to bring goodness to our families, communities, and the world.

Rabbi Stewart L. Vogel

Temple Aliyah, Woodland Hills